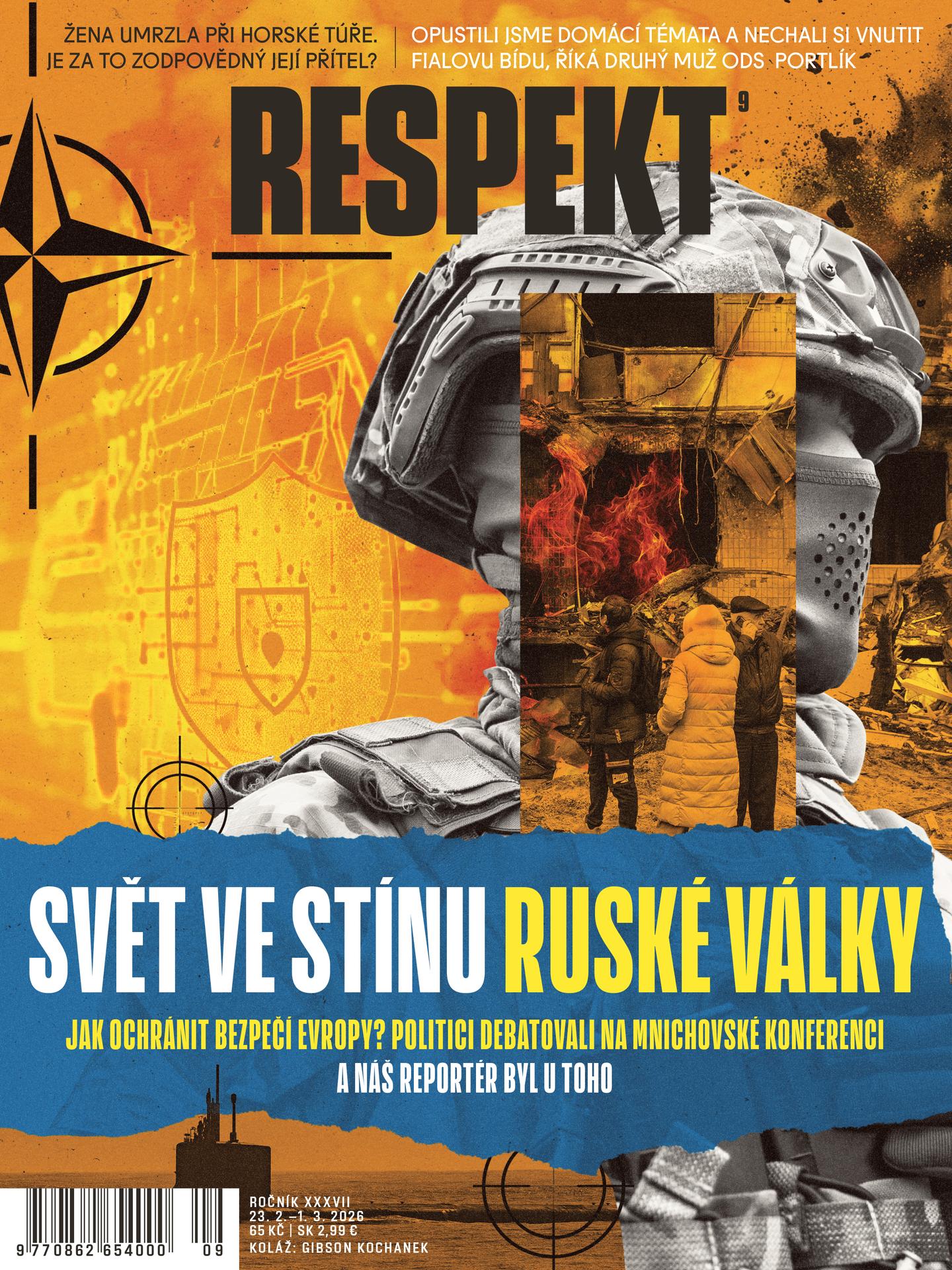

How to Contain Smog

The “dirty North” is looking for a recipe to improve inhabitants’ breathing

For a long time, it seemed that dirty air was not among the things that would get Czechs riled up. Fifteen years ago, under public pressure, local firms mounted sulfur traps in their chimneys and all were satisfied. The fact that many dangerous poisons remained in the air even after this change, hardly bothered anyone for years. But now it is over.

Winter inversions have suggested that for several years now, and this year the pressure exerted by discontented residents, especially those from the contaminated Ostrava region, is showing its first results. Unbreathable air moved from scientific tables to the government agenda last week. We still do not know the results, and the day the Czech Republic sheds its reputation as the country with the most polluted air in the European Union is a long time coming. Nonetheless it is a revolutionary change.

Big mistake

On one side, the view of the snowy plains dotted with villas and family houses gives the impression of absolute idyll. On the horizon, the woods are turning black, which contrasts with the white winter sky; children are sledding on one of the slopes. But do an about-face and everything is different. The sky is painted a sickly yellow and silhouettes of chimneys loom over the tops of trees. And after a while, even one’s lungs get the feeling there is, after all, something to the reports on local air quality – according to the numbers, the worst in the EU.

Ostrava’s Radvanice a Bartovice district was just unlucky enough to have Communist planners build a huge steel plant next to it. The location to which Ostrava’s elite moved for its clean environment during the First Republic became a hell on earth overnight. The everyday reality included a haze made of industrial waste products and, according to locals, soot raining down from the skies so thickly that you could not see the step. After the Velvet Revolution, the airit seemed that better days were on the way.

“We relied on the idea that the environment would just keep getting cleaner and cleaner,”

says Radvanice native

Vladimír Burda

before his family villa, which his grandfather had built during the First Republic.

“We only admitted that it was a mistake a few years ago,”

he added. While soot no longer fell from the sky, at the turn of the millennium, however, the steel mill started ramping up production again, especially after the global steel giant ArcelorMittal bought it. And it became clear to the locals that unless they start exerting some pressure, cleaner air was not going to come by itself.

The numbers spoke, and they speak clearly. Each year, pollution from airborne dust, to which carcinogenic substances binds, exceeds the legal limit many times over. And that’s not all – the air is also filled with sulfur dioxide produced by cars, as in other densely populated conurbations in the Czech Republic.

The biggest polluter in the area is ArcelorMittal. The company understandably did not start out with a focus on environmentally friendly operations, it was less than forthcoming about the quantity of toxic substances it was contributing to pollution, and regional officials tolerated it just to keep the biggest employer (employing some six thousand people and a number of smaller firms in the region are dependent on it) from moving its operations to neighboring Poland or somewhere farther east. “So we had to start to fight for better air ourselves,” says Burda. The fight was started by local pediatrician Eva Schallerová, who proved from her patients’ medical records that the local children were thirty times more apt to suffer from asthma than in other parts of the country. That was enough to captivate some of her fellow residents, who after a while formed a civic association called simply Vzduch, or Air, which set its sights on pressuring Mittal to clean up their operations.

Third time bad luck

“It’s a little like banging your head against a brick wall, according to all the numbers we have, the air just does not improve,” says Mr. Burda, one of the heads of the civic association (in a village with six thousand inhabitants, it has 300 members). Even so, things started to get better. ArcelorMittal initially refused to respond to the dissatisfied public at large. But today, in accordance with the times, it proudly reports that it has begun investing billions into new dust filters, which should reduce the discharges of dirt by seventy percent once they’ve been installed in two years’ time.

Mr. Burda’s skepticism is nevertheless appropriate. As experts point out, the unbreathable air is not just because of one factory, although it does have the lion’s share. There is always a combination of multiple sources – growing traffic and what unscrupulous people put in their heaters should be added to the big factories. If the air is to improve, all three sources must be radically purified all at once.

But a lone civic association cannot change that. The city, region and state all must get involved.

A different region

“I came to Ostrava from Eastern Bohemia at the end of the eighties,” says Libor Černikovský, Chief of the Air Quality Division of the Czech Hydrometeorological Institute in Ostrava. “And the environment is much better here than it was back then,” he adds. “But for some reason, this region has bad luck.”

In reality that misfortune looks like this: a lot of people in one place (Ostrava and Karvina are basically one unit), heavy industry and hundreds of small local heaters. Then, all it takes is an inversion and the concentration of pollutants in the air begins to grow radically, as not only the people of Ostrava have seen in recent weeks but also the people of Prague and Brno (the latter mainly because of dense automobile traffic).

In order to be able to breathe better even during an inversion, all sources of pollution have to be restricted throughout the year. In Prague and Brno, it would suffice if more people rode public transportation or walked. That has yet to happen, and in Ostrava they need on top of that billions of dollars of investment in cleaner technologies in the other big factories, as well as investments in private households so they’ll heat their homes to the cleanest possible way.

“It’s a fact. We have to address transportation, large enterprises and households all at once,” said Dalibor Madej, Ostrava Councilor for the Environment, over an air quality analysis, which the city had drafted after the citizens’ protests two years ago. Pollutants from highway traffic should be eliminated by bypasses around major cities and promoting public transport, large companies in the region should reduce their annual emissions by around fifty percent, and the Region of Ostrava came out with a bill that would allow officials to inspect what people are burning at their homes.

Everything is still only on paper and even if they could meet all the plans, the people of Ostrava will continue to breathe the dirtiest air in the Czech Republic thanks to their region’s “misfortunate” conditions. “We know,” said Councilman Madej. “To improve this, we’d have to completely change the structure of industry here,” he added. The region should be looking for inspiration in the Ruhr area of Germany, which is gradually changing from a region of mines and steel mills into a place where cutting-edge technology and university research reigns supreme.

Ostrava is pointed in this direction. The local university is growing, in addition to the planned new medical school there, within three years there should also be an advanced computer center with one of the hundred most powerful supercomputers in the world, and Ostrava is seeking the prestigious title of European Capital of Culture (held now by a city in the Ruhr area of Germany). “We are trying to attract attention to ourselves simply as a region that is changing and offers interesting opportunities. This is the only way we’ll be able to breathe better here one day,” Councilman Madej evaluates a modest start.

Rapid process of airborne dust mainly affects children, increases the number of inflammatory diseases and binds to carcinogenic substances. Despite that, it has long been ignored here in the Czech Republic, and even at the beginning of the millennium here there were no rules defining unacceptable concentrations of airborne dust. Now, the permitted maximum daily concentration of airborne dust (PM10) is 50 micrograms per cubic meter of air. By that concentration may be exceeded five times a year. In Radvanice and Bartovice, for example, last year the possibility for exceeding the legal limit was exhausted as early as February. And the daily concentration in recent weeks has exceeded the standard by up to nineteen times.

Photo caption | Comrades and industry, thanks!

Photo author | Milan Jaroš

Pokud jste v článku našli chybu, napište nám prosím na [email protected].